I AM A SALT LAKE

Exhibited in I am a salt lake, The Physics Room, Ōtautahi Christchurch, curated by Abby Cunnane

Ana Iti’s film brings together footage from Kāpara-Te-Hau (the salt lakes in Te Tau Ihu), abstracted diagrams drawn on glass, and a first person text. These three elements recur, something like the pattern-based process of learning where you repeat a sentence or bar of music until it is embodied, becomes part of you. I am a salt lake also registers the difficulty of finding language sufficient to articulate the relationship with the different whenua, seas, lakes, winds, houses, that the artist passes through.

The work is grounded in Kāpara-Te-Hau, a specific geographical site and system: the climate, conditions, and industrial processes that produce salt. Kāpara-Te-Hau is near where the artist grew up in Te Waiharakeke Blenheim. Returning over the past year for this research, Iti parked the car at the end of the road nearest the sea, moving slowly inland toward the lake, with frequent stops to film and record audio. The physical environment there is harsh. It is a wide shallow basin with no tributaries, limited rainfall, and hot dry winds, all of which make it ideal for salt production. In this process seawater is pumped from the ocean and gradually transferred through a number of gated ponds until it becomes so concentrated and salty that it crystallises, and can be harvested and processed. Salt production has been operating in the region since 1952, and currently accounts for about half of all the salt used in Aotearoa.

The name Kāpara-Te-Hau holds older stories. Rangitāne kōrero in the area records a conflict between their tupuna, Te Hau, who came on Ārai-te-uru waka, and Kupe. Their battle left a physical impression in the landscape, and Te Hau’s kūmara gardens were inundated by a lake. Other pūrākau record the Kāhui Tipua, giants who lived in Wairau Marlborough and were also devastated by Kupe swamping their villages. Later, Te Rauparaha was temporarily captured here by Tuhawaiki, escaping to a longboat offshore by hiding in the kelp beds. During WWII the land was claimed by the government to be used for pilot training, and an airfield and bombing range were established. In 1943 the Christchurch businessman George Skellerup (who required a local source of salt for rubber recycling) received a licence to manufacture salt, and construction of the ponds started. Iti’s work doesn’t set out to explicitly tell any of these stories. However, it suggests that processes of sedimentation, documentation, or remembering, are both ecological and social. Accordingly, histories may be understood as residual within the landscape, leaving their own layers of sediment. I am a salt lake recognises the salt—and by extension other wai, or waters that carry it—as one such layer or record.

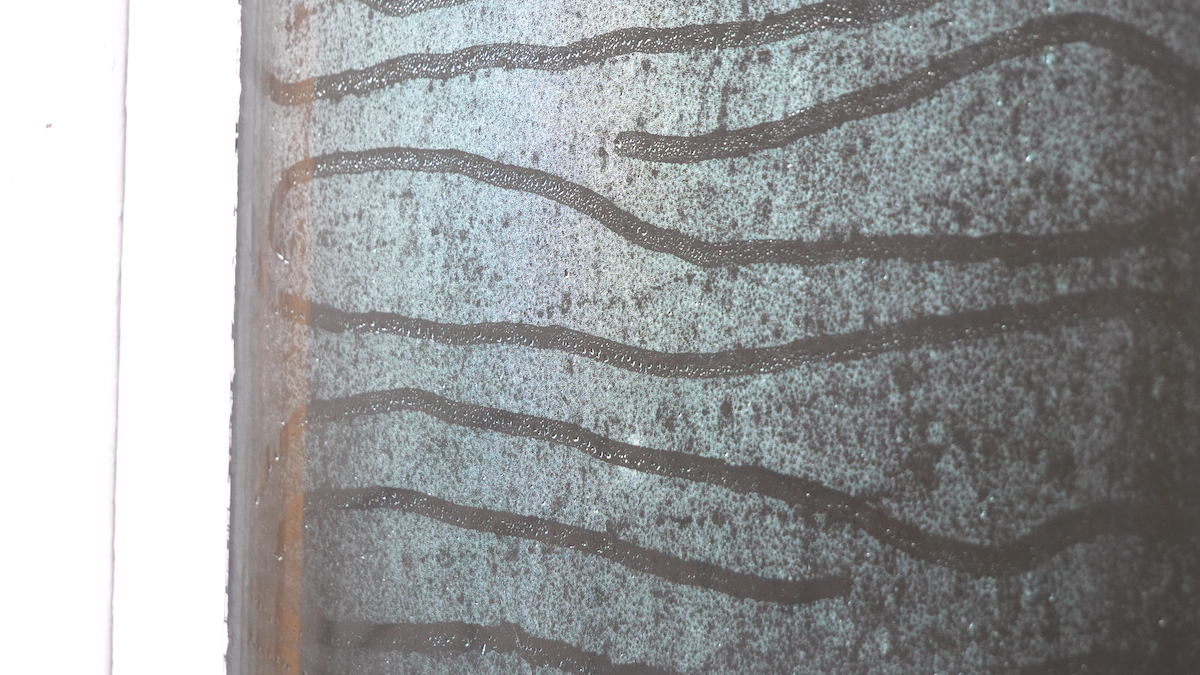

In the work Iti draws lines on a glass windowpane, which is semi-opaque with condensation. Watching these lines being slowly drawn can also feel like watching someone think, or like watching ribs as they rise, pause, and fall with breath. This part is filmed in Heretaunga Hastings, where the artist has recently relocated—another line of movement subtly documented in the work. It’s hard to make out the figure of the artist behind the glass, yet perhaps only too easy for many people who’ve lived in old wooden houses in Aotearoa to imagine the slightly damp interior air in the morning, the way that water sits on the inside of the windows when you wake.

The abstract diagram Iti draws alludes to the movements of wind and water, the settling of salt and alluvial sediment in layers, the evaporation process as the sun’s heat hits the water, increasing the mineral saturation. The window functions as a membrane or skin between viewer and the subject, as well as a physical barrier between the weather outside and the sheltered space inside. As a parallel idea, the projection screen in the gallery is both a wall which separates us from the interiority or ‘world’ of the work, and an opening into it. One reading of the work suggests that this tension—possible intimacy, and insurmountable distance— is a condition inherent in human relationships. The result is a sense of melancholy, immense solitude, or of deep thought that evokes homesickness. Iti mentions imagining Te Hau, whose whanaunga continued down Te Waipounamu while he stayed in Te Tau Ihu, looking at the cold horizon and thinking about the distance that stretched between them.

Lines of black text on a white ground appear intermittently throughout the work, intimate as a voice. I am trying to connect across two islands and a strait, the first says. As a whole the work reiterates this desire to span distance, both spatial and temporal. It may refer to a time when the ocean itself was home, spreading myself between the land and the sea, or, simply to an artist making decisions about what to do next: lifting and holding others’ things above me. Difficulty is implicit in the artist’s text, the difficulty of making sense of a place that both calls to, and troubles you. How to connect with a landscape that can appear hostile to human inhabitants, exhausted by processes of mineral extraction, as well as to connect to home, and to oneself? I am trying to fill myself up all the way, it says. Visiting the site for filming, Iti experienced the ruthless glare of the light-on-salt, the dry winds, ending the days with sore and tired eyes.

The salt itself—necessary to the human body’s nerve impulses, for muscle contraction and relaxation (including for the heart and blood vessels), fluid balance—is a second ‘voice’ within the work. It has a vitality of its own, as well as inherent life-giving properties. Initially dislocated from the sea, and then from its soluble state in water, the salt becomes a material thing, or a visible body, an ‘I’ rather than part of a moving interconnected whole. Perhaps it is the salt itself which asks the series of questions punctuating the work: how will I go there? how will I go? how to stay safe? These questions aren’t resolved at the end of the work. Rather, there is a sense that they will incrementally shift over time, dissolve with seawater, dry, and crystallise again.

- Abby Cunnane

Single-channel HD video, colour, sound, duration 12 mins 35 secs